A few days ago I was talking to a [traditional] marketer I deeply admire about performance analytics in offline marketing. She told me they simply look at the sales figures after the campaign and if they are increasing the team would conclude that the campaign is successful. Makes sense, right? Well, if you’ve been reading my blog you know there’s always a catch…

What’s wrong with looking at numbers and attributing the trend to certain actions?

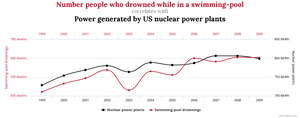

First the human tendency of taking separate and unrelated facts and forcing a logical link, an arrow of relationship upon them – so called Narrative Fallacy.

You probably also heard of “correlation doesn’t mean causation” – that’s about the same story.

The sales growth in the example can be as likely attributed to a competitor going out of business, seasonal changes, increase or decrease in per-capita spending, celebrity endorsement and various other factors. So be careful jumping into conclusions.

The second caveat is the Regression to the Mean. Had an unusually good month? Expect to have a worse month after. The Sports Illustrated jinx is an excellent example of regression to the mean. The jinx states that whoever appears on the cover of SI is going to have a poor following year (or years). But the “jinx” is actually regression towards the mean.

So before you are going to declare that you hit that “tipping point” and that “viral growth” after an extremely good season think regression to the mean.

The third problem arises when you are dealing with small sample sizes. Did you run your campaign long enough and exposed to a large enough group of population to be sure that your results are not simply due to a random chance?

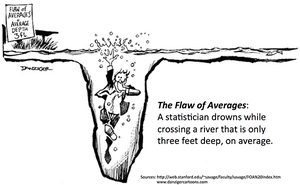

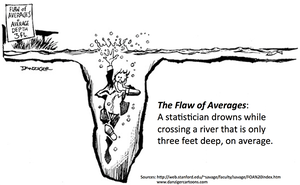

Beware of averages and aggregated data.

What drove your increased aggregated performance this month can simply be an outlier. Think of a large group of people who came to dine at your restaurant to celebrate something and made your monthly sales for the month.

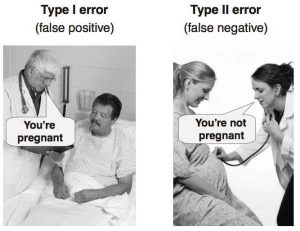

Remember of False Negatives and False Positives – do not make conclusions on incomplete data.

And next time you sit down to analyse your numbers, remember: if you torture the data enough, it will confess.